|

| In the mid-nineteenth century, first American consul to Japan Townsend Harris shocked Japanese by walking straight into the shogun's presence in Edo Castle without removing his shoes. Foreign visitors unfamiliar with Japanese customs even today can just as easily startle or even anger their hosts by walking into a home without taking off their shoes at the door. One of the peculiarities of the Japanese home, in fact, is that outdoor footwear are left at the door, and most Japanese cannot imagine wearing shoes in the house. The custom is deep-rooted and has not changed despite the widespread shift in the typical lifestyle from that centering around tatami-mat floored rooms to Western-style interiors furnished with tables, chairs, and beds. No matter how tiny the apartment or how westernized the home, people take their shoes off. Where do they take them off? What do they do with their shoes? Why do Japanese remove outdoor footwear? Below we introduce the results of a questionnaire surveyed by the Living Design Center Co., Ltd. filled out by 100 Japanese answering these questions. |

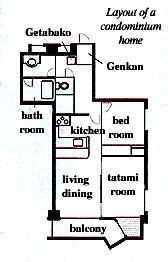

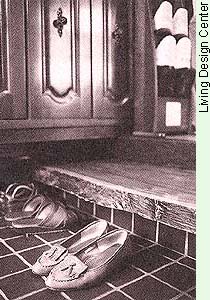

Where are shoes removed ? Inside the door of a Japanese house or dwelling, you find an entrance way called the genkan is considered an important place, perhaps not so much in a small apartment, but very much so in ordinary condominiums or single family dwellings, as the " face " the household shows the world outside. There are many kinds and sizes of genkan, and usually the hallway or entrance hall beyond it is one step higher. As a general rule the smaller the genkan the lower the step. When there is frequent traffic in and out of a house, shoes mat be lest right in the genkan, and usually it is equipped with a geta-bako, or shoe cupboard to put away unused shoes. Nearby, as one steps up into the house, there is likely to be a slipper rack, holding pairs of slippers to be worn in the house. The survey showed that 98.9 percent of respondents use slippers in their homes, although they are not worn into the rooms floored with tatami because the scuffing easily damages the surface of the mats. A separate set of slippers is provided for use in the toilet. In this way, not only is there a clear distinction between inside and outside of a home, but within the home as well between tatami rooms and wood or carpeted floors, and between the toilet and other parts of the house. Inside the door of a Japanese house or dwelling, you find an entrance way called the genkan is considered an important place, perhaps not so much in a small apartment, but very much so in ordinary condominiums or single family dwellings, as the " face " the household shows the world outside. There are many kinds and sizes of genkan, and usually the hallway or entrance hall beyond it is one step higher. As a general rule the smaller the genkan the lower the step. When there is frequent traffic in and out of a house, shoes mat be lest right in the genkan, and usually it is equipped with a geta-bako, or shoe cupboard to put away unused shoes. Nearby, as one steps up into the house, there is likely to be a slipper rack, holding pairs of slippers to be worn in the house. The survey showed that 98.9 percent of respondents use slippers in their homes, although they are not worn into the rooms floored with tatami because the scuffing easily damages the surface of the mats. A separate set of slippers is provided for use in the toilet. In this way, not only is there a clear distinction between inside and outside of a home, but within the home as well between tatami rooms and wood or carpeted floors, and between the toilet and other parts of the house. |

Genkan |

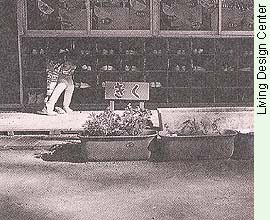

Getabako at kindergarten |

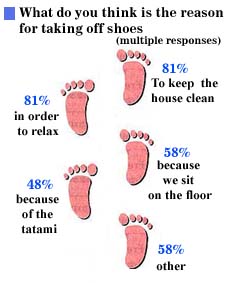

| Why Remove Shoes ? The custom of removing outside footwear within the house goes back at least as far as the Heian period ( 794 - 1192 ) among the upper classes and gradually spread thereafter throughout society. One of the reasons that footwear was shed in this fashion was because of the high rainfall and the generally very damp climate. A house would be quickly dirtied if people walked in wearing mud-covered shoes or sandals. But probably what came first was the custom of both sitting and sleeping directly on the floor on straw mats or cushions laid over it. Footwear was removed at the entrance to help keep the house clean.  Traditional footwear consisted of straw sandals, which allow for ample circulation of air to the feet, or clogs ( geta ) or sandals ( zoori ) made of wood or plaited cloth. After the Meiji Restoration ( 1868 ) as Western lifestyles were adopted, shoes gradually became the dominant form of outdoor footwear, but shoes actually do not permit enough air passage for comfort in Japan's humid climate. This is another reason that the custom of removing shoes indoors did not change. Traditional footwear consisted of straw sandals, which allow for ample circulation of air to the feet, or clogs ( geta ) or sandals ( zoori ) made of wood or plaited cloth. After the Meiji Restoration ( 1868 ) as Western lifestyles were adopted, shoes gradually became the dominant form of outdoor footwear, but shoes actually do not permit enough air passage for comfort in Japan's humid climate. This is another reason that the custom of removing shoes indoors did not change. The practice of taking off shoes indoors is in fact very widespread in Asia, not only in Japan, but in Korea, the Jiangnan province of China and from Indochina throughout the Southeast Asian archipelago where it is also common for dwellings to be elevated off the ground. The development of the genkan space, with its shoe storage cupboard and other accouterments, as a formal space where shoes are removed, is probably a reflection of the Japanese sense of cleanliness. It also is a space that satisfies the Japanese impulse to clearly separate inside from outside. Returning from outside, the act of removing one's shoes is associated with relaxation within the home. Indeed, the answer to the question about why shoes are removed in our survey second only to "to keep the house clean" was "in order to relax." The practice of taking off shoes indoors is in fact very widespread in Asia, not only in Japan, but in Korea, the Jiangnan province of China and from Indochina throughout the Southeast Asian archipelago where it is also common for dwellings to be elevated off the ground. The development of the genkan space, with its shoe storage cupboard and other accouterments, as a formal space where shoes are removed, is probably a reflection of the Japanese sense of cleanliness. It also is a space that satisfies the Japanese impulse to clearly separate inside from outside. Returning from outside, the act of removing one's shoes is associated with relaxation within the home. Indeed, the answer to the question about why shoes are removed in our survey second only to "to keep the house clean" was "in order to relax." |

| Q1 : What do you think of the custom of taking off your shoes when entering a Japanese house ? | ||||||

| 1. | Very good | 81% | ||||

| 2. | Cannot say | 17% | ||||

| 3. | Not good | 1% | ||||

| 4. | No answer | 1% | ||||

Reasons for " very good " reply | ||||||

| Maintains cleanliness in the house | 27 | |||||

| Gives a sense of liberation (can relax) | 23 | |||||

| Suits Japan's climate and customs | 20 | |||||

| Good for healthy feet | 14 | |||||

| Draws the line between inside and outside (private and public) | 13 | |||||

| Wonderful Japanese traditional culture (daily life culture) | 5 | |||||

| Can directly feel the floor with the feet | 4 | |||||

Q2 : Why do you think the Japanese have this custom of taking off their shoes ? ( multiple response ) | ||||||

| For the sake of cleanliness | 81% |  | ||||

| Because they want to relax | 81% | |||||

| Because they sit on the floor | 58% | |||||

| For the sake of the tatami mats | 48% | |||||

| Others | 58% | |||||

Other reasons | ||||||

Custom and climate Custom and climate | 9 | |||||

To draw the line between inside and outside (private and public) To draw the line between inside and outside (private and public) | 8 | |||||

Because it is a custom Because it is a custom | 4 | |||||

To directly feel the floor with their feet To directly feel the floor with their feet | 2 | |||||

Because they are Japanese Because they are Japanese | 2 | |||||

Because it is a sacred place with a miniature Shinto shrine shelf or Buddhist household altar Because it is a sacred place with a miniature Shinto shrine shelf or Buddhist household altar | 1 | |||||

Because it makes floor maintenance easier Because it makes floor maintenance easier | 1 | |||||

Source : Living Design Center | ||||||

| School Shoes are also removed at school. There is a large entry vestibule equipped with shelves or lockers for each student's shoes, where they change from outside footwear to inside shoes. Changing to indoor footwear is the rule in all schools in the Tokyo metropolitan area. Since there is an assigned cubbyhole for each student, sometimes other things besides shoes may be left there, such as love letters, as often depicted in popular girls' comics stories. Not only in schools, but in places closely associated with tradition such as shrines and Buddhist temples, in some clinics and hospitals, as well as in Japanese-style restaurants, shoes are taken off, but are worn in such places as university buildings and most business offices. Genkan etiquette Learning the proper way of leaving one's shoes in the genkan is part of the manners every child learns. When visiting someone else's house, it is proper to turn around after stepping up into the hallway, and align your shoes, placing them to one side. Before you leave, you will find they have been turned around and placed in the center, where you can slip into them easily as you depart. |

Turning a guest's shoes |

| Shoes The cultural influence of China on Japan during the Nara (710-794) and Heian (794-1185) periods fueled the development of zoori, flat thonged sandals made of straw or leather, and geta, wooden clogs. Most Japanese of the Kamakura (1185-1333) and Muromachi (1333-1568) periods wore zoori or, when making long journeys on foot, waraji rough straw sandals. Geta became popular among city dwellers during the Edo period (1600-1868). Western footgear gained initial acceptance during the Meiji period (1868-1912) and became the norm after World War II. Today zoori are worn only on special occasions as part of a formal kimono ensemble, and geta are worn almost exclusively with traditional casual clothing such as the yukata. |

| Various Shoes | ||

Zoori |

Geta |

Waraji |

High-heeled shoes |

Shoes |

Sneakers |

|

Original text : The Japan Forum Newsletter no8 "A day in The Life" June 1997.

Send feedback to forum@tjf.or.jp