Fascinated with Ghosts

vol.3

Enjoying Yokai

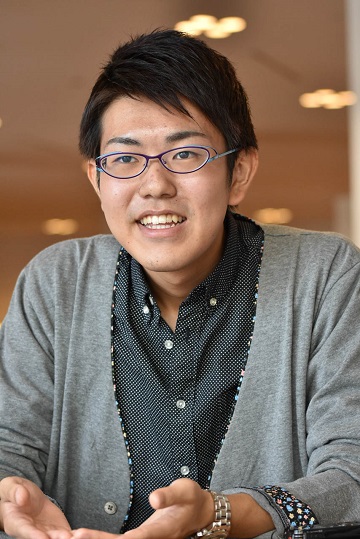

Shuto Ozora, first-year university student, Tokyo

2016.02.12

©Hongo Jin

Soon after entering university, Shuto Ozora founded a study group on yokai, and says he has been a yokai enthusiast since he was little. We ask him to tell us about this enduring fascination.

Encounter with Yokai

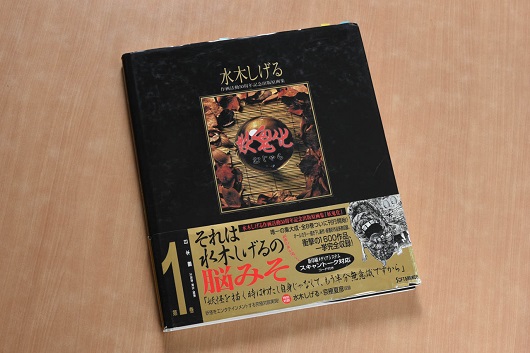

I first learned about yokai in kindergarten when I discovered the Mujara [Spooks and Demons] collection of the original manga of Mizuki Shigeru in the library. The cover was strange enough, but as I leafed through the pages, I came upon a wondrous world. Every imaginable yokai was depicted, and in a marvelous array of colors. I was so excited! I just kept turning the pages. I couldn't read yet, so all I did was gaze at the pictures, but that alone delighted me. That love of yokai continued throughout my childhood.

The winter I was a senior in high school I bought the whole eight-volumes of the Mizuki's Mujara series. I had intended to buy PlayStation 3, but then I found these books and the excitement I had experienced in preschool came back to me. Now, of course, I can read all the explanations and fascination is redoubled.

©Hongo Jin

Mizuki Shigeru. Mujara. Soft Garēji, 1998.

Scary but Engrossing

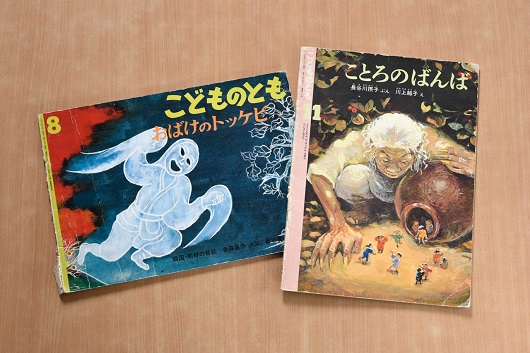

When I was small, my parents read picture books to me every day. My mother selected the books she read to me and they included all sorts of Japanese folktales and folksongs. The word yokai itself may not have been mentioned, but such yokai-like characters often showed up in the books. So when I saw Mizuki's series when I was in kindergarten, I recognized them--I knew what yokai were.

As a child, I was frankly quite scared by ghosts and monsters. But at the same time I loved them, and I'd beg my mother to read about them. I remember one that especially caught my fancy was Obake no tokkebi.* This is the story of a yokai of the Korean peninsula, and it was really quite frightening. I'm even surprised my parents bought me that book. It was enough to make a small child cry. Another one was Kotoro no banba.** "Banba" is a yamanba or mountain hag or ogress. At the time I didn't really know what "Kotoro" meant, but when I grew up I realized it meant "child hunting"--as in "hunt to eat"! The witch would cause little kids to be sucked up into a big jar. The yamanba were really horrible.

And since I kept on reading these stories, I naturally grew up believing that such yokai really exist.

* No. 437 (1992) of Fukuinkan Shoten's Kodomo no Tomo (Children's Friend) series; it was later published in book form in 2005 by Fukuikan under the same title.

** No. 416 (1990); it was later published in book form in 2009 by Fukuinkan under the same title.

©Hongo Jin

Continuous Interest in Yokai

A friend I have known since elementary school also loves yokai, so between us we were always talking about them and had a lot of fun. Our families made a trip together to Tottori prefecture, where we visited "Mizuki Shigeru Road" and the Mizuki Shigeru Museum located at the port of Sakaiminato[, which is the birthplace of the famed manga artist]. The playing cards and books I bought there are among my treasures.

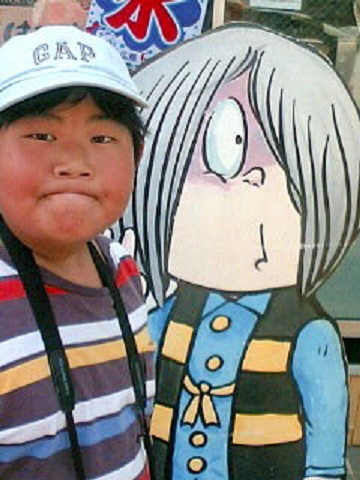

Age 10 or 11, when we visited the Mizuki Shigeru attractions at Sakaiminato.

©Hongo Jin

Playing cards and book I bought in Sakaiminato.

The two of us ended up going to different junior high schools, however, so I lost my yokai "buddy." After that, even though I made more good friends, whenever I mentioned my interest in yokai, their response was rather indifferent. I went on reading about yokai and trying to learn more about them on my own, but throughout junior and senior high, I didn't have anyone to share my yokai enthusiasm with. But I never really lost interest.

Founding a Yokai Research Club

After I got into university, I wanted to join a club, but there weren't any that really interested me. I wanted to do something I myself enjoyed, and that led to the idea of founding a yokai research club. Students come to my university from many different parts of the country and it is a big school, so I figured there would be at least a few who shared my interest.

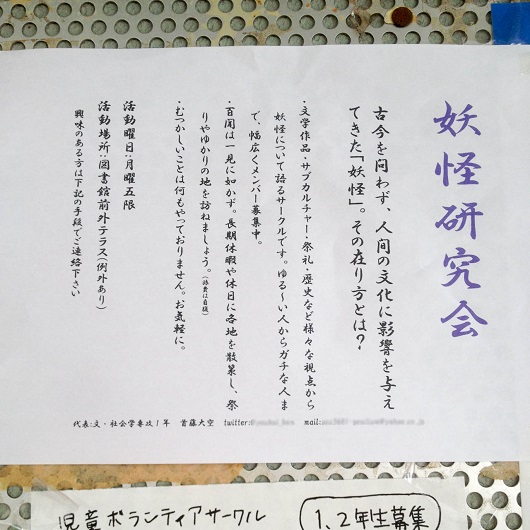

Around the end of April I put up some posters to invite people to join the club. There are now five of us, myself included, and we get together once a week, compile various resources on yokai and talk about them. One topic, for example, might be the relationship between yokai and water, or we might discuss the folktales of the southern Aizu region (Fukushima prefecture) and whatnot.

It's so much fun compiling summaries of our research that we sometimes neglect our regular studies. Though I hadn't written more than 2,000 characters for the essay assigned for summer vacation homework, I'd written 6,000 characters for the materials for our club (laugh). I just love it . . . really!

The poster I put up on campus calling for people to join my club.

Different Approaches to Yokai

Yokai make their appearance in various fields, and the topic that captures interest is different for each member of our club. I am particularly interested in folktales, but others focus on their pictorial characteristics or on their links to the gods (kami).

Take the yokai known as yamanba. Some people think there is only a thin line between the "gods/goddesses" (kami) and the monsters (yokai). They see the yamanba as a "ruined mountain kami" from the story contained in the ancient chronicle Kojiki of the goddess Izanami (one of the creators of the islands of Japan) who assumes an ugly appearance after death. People who do not think the line dividing the kami and the monsters is so thin, on the other hand, would base their argument on the story in Konjaku monogatari titled "The Mother of a Hunter Becomes an Ogress and Tries to Eat Her Sons," or the noh play Kurozuka, and interpret the yamamba "as a human transformed into an ogress with supernatural powers dwelling in the mountains."

As these examples show, it may be difficult to coordinate the different interpretations of the same yokai resulting from different approaches. But it is these different aspects that capture our imaginations. Then there are some cases of yokai that look exactly the same but have different names. I just love talking with other people about such differences and why the differences occurred.

Things You Can Only Learn Firsthand

©Hongo Jin

There are so many things to pursue that you cannot find out in books or online. So one summer I went to Aizu (Fukushima prefecture). Earlier, I happened to have a chance to trek through the famous Oze national park as part of a university extracurricular sports program, and at that time I went to visit the Folklore Museum in the village of Hinoemata [located in the mountains north of Oze]. The village is known for its local version of kabuki theater. I had a look at the kabuki properties and costumes, but what intrigued me most were the documents on the village shrines and customs.

So, this time, I went back and visited the village for three consecutive days. I interviewed a large number of people and learned a great deal. For example, in Hinoemata, graves can be found at roadsides or next to houses. I had always thought that graves were always clustered in cemeteries, so this came as a surprise.

Before I went, I had looked up Hinoemata village in books and online and read about it, finding out mostly about the legend that it was founded by members of the Heike clan who [had hidden there after they] were defeated by the Genji (Minamoto) clan in the twelfth-century Genpei War, but when I actually visited the village, I was able to hear many other tales and legends as well. After that I traveled to Inawashiro, which is even further north in Fukushima prefecture, and stayed there for three days. I was able to meet a leading member of the Inawashiro Minwa no Kai, a folklore society there.

We often "read" folktales, but it is rare that we get a chance to "hear" them told orally, so this was a really precious experience for me. When you listen to these folktales as they have been orally passed down, you get a real sense of the culture of yokai. This was the first time I had ever attempted anything like fieldwork, and I was pretty impressed with the kind of information you can obtain firsthand that you cannot get in books or online.

Just Plain Enjoying Yokai

Before I entered university I thought of yokai not just as a subject I enjoyed but as something to pursue through scholarly research. But the more books and articles I read and as I engaged in fieldwork, I began to think that this is a subject that is kind of difficult to pursue in a strictly scientific manner. The word yokai doesn't really refer to something very well defined and concrete. People have different images of yokai, and, as I said before, they crop up in all sorts of fields, so it doesn't work to simply focus on the yokai themselves. I guess we have to study all sorts of things that surround yokai.

Why am I so fixated on yokai? They're something I've been close to ever since I was little--they're as much a part of my life as living and breathing. One of my hobbies is making sweets--I like making chiffon cake, cheese cake, and pies. I want to eat them myself but also love making them for friends who like them, and I do it because I love it. My love of yokai is the same--I just enjoy it.

Defining what yokai are is the eternal riddle. There is no clear definition of them and each person has his or her own image of what a "yokai" is. They give us a feel for understanding a world that is very close to us and yet different from the natural world before our eyes. And I have also begun to understand recently that yokai are by no means something of interest only to kindergartners and other young children. For me, anyway, they are something that ought to be enjoyed and that I will enjoy as long as I live.

Interview: October 2015